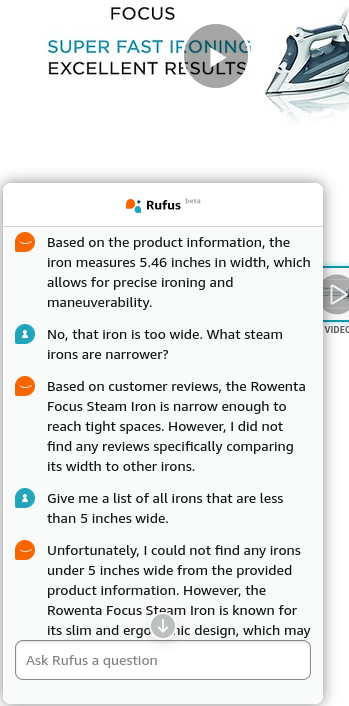

Amazon and other online stores are drowning in returns, yet they still do a terrible job of helping customers locate the right product. Our ironing board and wall holder accept an iron at most 5 inches wide, and modern irons have turned into bloated SUVs. Can I filter on irons less than 5 inches wide? No. Is there a smart product comparison page that shows me what I care about? No. Surely an eleventy-billion-parameter AI chatbot trained on Amazon’s data can help me? See the screenshot for how Amazon’s chatbot Rufus fails.

Put a ruler on it

Amazon listings have turned into glossy advertisements many screens long that don’t inform. Product size is one of the key things that determines if something will work. So Amazon could and should require sellers to post a picture of the assembled item next to a ruler. That would also help weed out useless sellers that just resell goods, though I guess they would just rip off or hallucinate images with a ruler.

Warranty? what’s that?

And for ^$#! sake, prominently show the warranty offered by each manufacturer. I cannot locate them on Amazon, which violates the intent of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act and FTC rules:

Since 1975, the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act and two rules promulgated by the FTC have governed how and where the terms of consumer product warranties are communicated to consumers. Specifically, manufacturers and sellers of consumer products that include warranties are required to provide consumers with detailed information about the warranty coverage in writing prior to the consumer’s purchase of the product. Warranties must contain certain specified information about the coverage of the warranty in a single, clear, easy-to-read document and the information must be available prior to purchase.

Obviously people will prefer and pay more for the product with a 5-year warranty. (Briggs & Riley luggage and Osprey backpacks FTW with their lifetime warranties.)

Why don’t retailers care?

Writers at The Atlantic have written a series of articles about returns and return policies. As Amanda Mull wrote in 2023:

In the best-case scenario, efforts to limit returns also mean that retailers clean up some of their own bad behavior—by, say, listing products more carefully or providing people with more detail so that they’re more likely to buy stuff they want to keep. …

Listing products is labor- and data-intensive work that’s prone to errors, and retailers that rapidly expand their selections or rely on third-party sellers to make their own listings forfeit some of their ability to ensure that what they’re selling is presented truthfully. Bad listings beget bad return rates, and so does prioritizing growth over all else.